|

About Cairn-Building |

–Cherokee proverb

September 28, 2018

The word "cairn" originates from a Gaelic term for "stone mound" or "heap of

stones". For millenia, such formations have served two purposes —

spiritual monuments and navigational markers. The most common usage of cairns

is to help keep hikers on the correct path. (The little ones also are known

informally as 'ducks' — probably because a little round stone

placed atop a bigger round stone can resemble the profile of a real duck.)

Occasionally, one might encounter a 'decorative' cairn somewhere, most likely created either out of boredom or because someone egotistically thought that it was 'cool' to leave his mark upon the landscape. I doubt whether a single such structure would excite anyone much; but lately, the practice has gone out of control, and the phenomenon is worldwide.

Nowadays, one can encounter areas in parks, and especially on certain beaches, where literally hundreds of balanced stacks of rocks have been erected for little reason other than to add to the growing collection. The result usually is an unsightly mess; yet even that is not so terrible, I suppose, provided that visitors know what to expect. Also, many people construct backdrops for Instagram selfies, then inconsiderately leave them behind.

The greater issue, though, involves remote areas that have been reserved as wild

and pristine places, where one supposedly is able to 'get away from it all' and enjoy

the natural beauty of our planet. That is why I go hiking, and I am not alone.

The proliferation of ego-substitutes has become so prevalent that many parks

and other governments have been compelled to outlaw it.

For example, the following directive was prompted because the Zion Narrows is

particularly susceptible to cairn-building. Lots of suitable rocks are

readily available there, and many tourists enjoying the lower end of the Narrows are

environmentally illiterate:

Those sentiments are echoed in the 1964 Wilderness Act, which specifies its guidelines as follows: "... A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain." It is further defined as "... an area of underdeveloped federal land retaining its primeval character and influence ... which is protected and managed so as to preserve its natural conditions..."

In simpler terms, it means that the act of defacing any such protected area with unnatural structures is a technical violation of federal law! How about that?

The problem manifests itself in several forms. Some possibly

well-meaning folk will build a cairn where a perfectly good trail marker

already exists, yet this serves only to clutter the landscape. Others

might alter or destroy an existing marker, causing hikers to go astray.

The greater issue, though, is the proliferation of cairns built as 'art' or

"I was here" reminders; yet nobody actually gives a damn whether someone else was there,

and one person's artwork can be another person's eyesore.

Some people claim that cairn-building provides them a valuable spiritual outlet, but leaving their 'religious' artifacts in an otherwise pristine location for the 'benefit' of others is pretentious bullshit. And amazingly enough, certain utter morons are of the opinion that they actually are "improving upon Mother Nature". In their cases, sterilization would effect such an improvement.

There also is the matter of upsetting the ecosystem. It is argued that

moving things around disturbs fragile vegetation or animal habitat, yet I admit to

being ambivalent on that score. Doubtless I have squashed many a bug underfoot

while hiking, broken a few branches, disturbed a few creek-bottoms,

and even trampled some flowers while off the trail; yet the world did not come to an

end. On the other hand, relocating a lot of rocks clearly does disturb

the soil, leaving an area more prone to erosion and possible landslides.

Many cairns do serve an important function, of course. Park rangers carefully

maintain trail markers in places where it is deemed necessary to assist

hikers — perhaps in a foggy area, or across deep snow, or through the

confusing slickrock mazes of southern Utah. Over near Medicine Bow Peak in

Wyoming can be found 4-foot rock cairns with 8-foot wooden posts sticking

out of the tops, constructed primarily to assist cross-country skiers.

In their cases the extreme size is necessary; in contrast, the markers in the Fiery

Furnace of Arches National Park are intentionally kept so small that it can be a

challenge just to find them. Navigational aids ideally are kept to whatever

minimum is required to get the job done; generally, a simple stacking of two rocks

(or sometimes even just one!) in a suitable location is sufficient to identify

it as a man-made signal.

Finally, some of the problem stems from a simple lack of education. Many

people out there simply have no understanding of the important function of trailside

cairns. When should somebody build one? Well, out in the wild, the answer

is: Never! The requisite hiker-assistance already is in place;

altering it or adding to it would serve no legitimate purpose.

It seems that Yours Truly also was in need of some education; for I had been treating encounters with remote 'cairn gardens' too lightly, especially in my hiking journals. My thanks to Cheri from Southern California for waking me up.

Although I never have made a habit of knocking down rogue cairns, that is going to change. I do become irritated when finding three or four ducks marking a trail in close proximity, despite the possible good intentions. Also, any excess of rock graffiti found in a wilderness location will be given the boot, just as if I were a park ranger.

Plenty of other information on this topic is available simply by typing "cairn controversy" into your browser's search engine. Make yourself knowledgeable, then help me to set an example.

There Is More to the Story

Having presented such a firm stance on the matter of cairn replication,

I feel the need to "fess up", though; for that is not the whole picture.

All of the hullabaloo is about cairns themselves — not just because of rampant

proliferation, but because they are in a special class and their time-honored

legitimate functions are being compromised. The issue is not with the stacking

of rocks per se, but about the numbers of such creations in potentially undesirable

places.

Piling stones atop each other is not the only way in which a backcountry visitor might alter the landscape, however. Check out the following images of some things that I have encountered on hikes:

Did any of those objects actually offend your delicate sensibilities? Not likely. How about these?

Your head still hasn't exploded? Well, mine hasn't either, even though those

human-made things all are technical violations of the Leave

No Trace philosophy; but did any of those artworks compromise my 'wilderness

experience'? Well, I certainly didn't suffer; in fact, I like finding such random

one-offs so much that I created the Trailside Anomalies page

just for them.

When a little girl spends hours designing a beautiful arrangement of

seashells, then leaves it for me to enjoy, I do it. That painted rock lay

unadvertised on a river bank with a million other rocks, for me to uncover; so

I did. The sticks on the sandbar disappeared when the spring runoff arrived;

and the Christmas decorations had been dismantled by mid-January, without a

trace. The environment wasn't harmed in the least, and neither was any person.

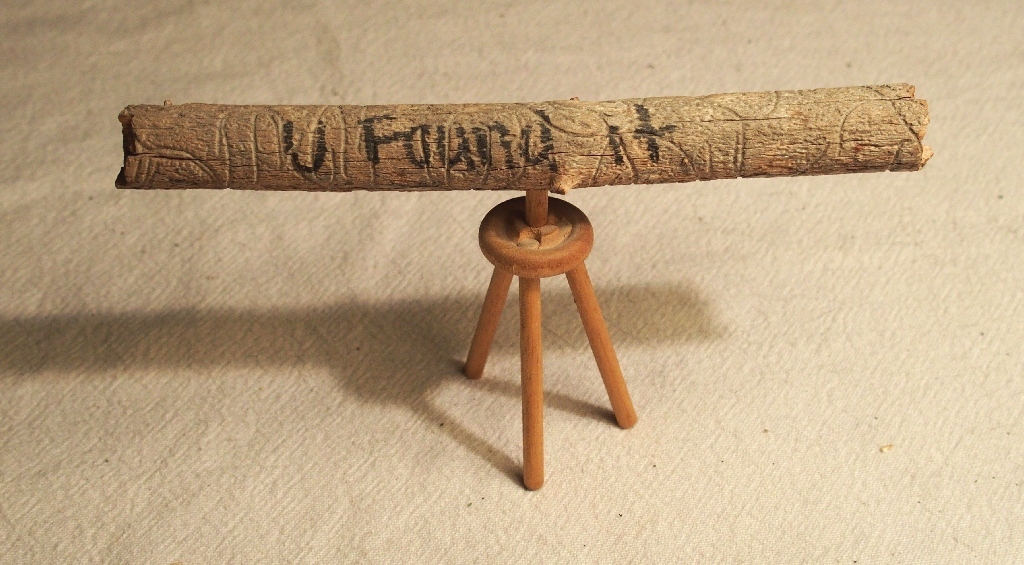

This one is my all-time favorite find (the three-legged stand is homemade):

Just waiting to be discovered, on the trail to Fresno Dome

Those little treasures simply are not the same as big, growing groupings of stacked rocks. They affect me in a positive way, as they would any sensitive person; and my camera looks forward to discovering a lot more of them.

I'll still kick down any inappropriate cairns, however. In fact, in October

of 2019 I did just that, knocking over about a hundred superfluous rock piles in the

slickrock country of southern Utah — mostly in Canyonlands

National Park. Enough is enough.